History of the Parish and Manor of Lilford

The full name of Lilford Parish is Lilford-cum-Wigsthorpe Parish. Lilford was also known as Lylleforde (XIV Cent.), and Wigsthorpe was also known as Wykenethorp (XIII Cent.) and Wykyngesthorpe (XIV Cent.).

Parish

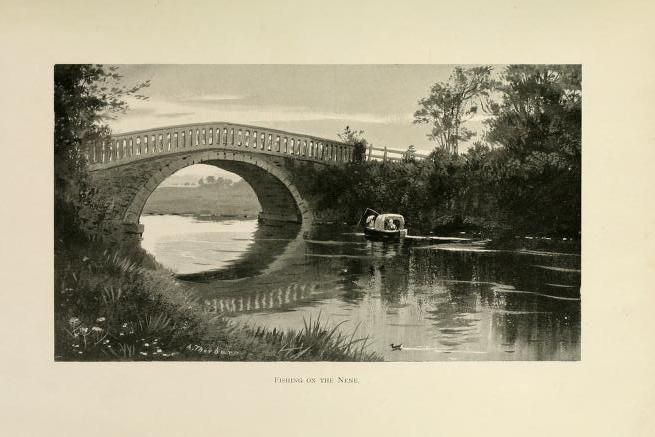

The parish, though included in the Hundred of Huxloe, is locally situated in the Hundred of Polebrook. It lies on the east bank of the Nene, which is spanned by a handsome stone bridge with fluted pilasters, erected in 1796 within a short distance of Lilford Hall.

.jpg) The hamlet of Wigsthorpe forms the eastern portion of the parish, the road from Thrapston to Oundle running between it and Lilford. The few houses which constitute the village are clustered round the old railway crossing in Wigsthorpe.

The hamlet of Wigsthorpe forms the eastern portion of the parish, the road from Thrapston to Oundle running between it and Lilford. The few houses which constitute the village are clustered round the old railway crossing in Wigsthorpe.

In the first half of the 18th Century, Lilford possessed a village of 12 houses and a church dedicated to St. Peter, and the hamlet of Wigsthorpe also held 12 houses. A fine soft spring of water to the south of Lilford Park marks what was once the centre of Lilford village.

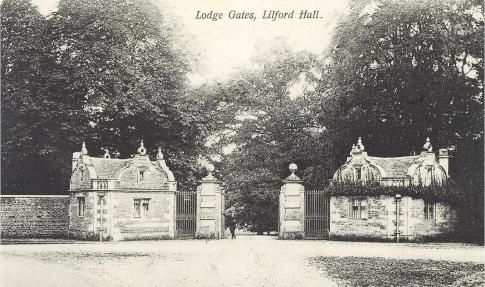

The greater part of the Lilford portion of the parish is occupied by Lilford Park. Lilford Hall lies near its western limit, and possesses an extremely charming view, across the Nene, of Pilton with its old church and manor house.

The Hall was originally built in 1495 as a Tudor mansion, but is now substantially a fine example of late Jacobean work built in 1635, this date appearing on two great chimney stacks in the court at the back of the house. The estate then belonged to the family of Elmes, and it was William Elmes, who succeeded in 1632 and died in 1641, who was the builder of the Jacobean part of the Hall.

The three principal fronts are treated in the traditional Jacobean manner, with mullioned windows and gables, some of which are straight in outline and some curved, the whole being disposed symmetrically; but the entrance front has no projecting wings, its line being only broken by a large semicircular bay window of two stories at each end, and a porch of one story in the middle. Wings project at the back and form a kind of court. This general disposition is indicative of the end of the Jacobean period. The architectural treatment is quite simple, but none the less satisfactory on that account. An unusual feature is the grouping of many chimney flues in a long straight row with separate shafts all joined together at the top.

The house stands well up above the adjacent river Nene and has charming prospects. Sir Thomas Powys, who purchased the property in 1711, decorated the interior in the fashion of the time. The upstairs drawing room retains its original character, and the main staircase dates from this period; but the entrance hall and corridor appear to have undergone alterations. There is one room, the library, where the oak panelling and a handsome oak chimneypiece of the early house still remain; otherwise the interior work is of the 18th century and later.

The stables at the rear form part of the architectural grouping. They are of the 18th century, simply but carefully planned and they add to the interest of the general arrangement. The gardens have been admirably laid out in modern times, and in conjunction with much fine old timber, form an attractive setting to the house. The aviaries attached to the house once contained a collection of rare birds.

The area of the parish is 1827 acres of land and 13 acres of water. The ground near the Nene is liable to floods, and nowhere rises to much more than 200 ft. The soil is clay; the sub-soil clay and rock. To the west of the Thrapston road it is good: to the east of it, cold and inferior. The chief crops grown are wheat, barley and beans. The population in 1921 was 164. (fn. 1)

The area of the parish is 1827 acres of land and 13 acres of water. The ground near the Nene is liable to floods, and nowhere rises to much more than 200 ft. The soil is clay; the sub-soil clay and rock. To the west of the Thrapston road it is good: to the east of it, cold and inferior. The chief crops grown are wheat, barley and beans. The population in 1921 was 164. (fn. 1)

The vicarage is annexed to the rectory of Achurch, where the rector, the incumbent of the combined churches, once resided.

The former Public Elementary School (mixed) was built about 1845 by Lady Lilford, and enlarged in 1866 by Lord Lilford to hold 90 children. The children attended from the adjoining parishes of Pilton and Thorpe Achurch.

Manor

In the time of King Edward the Confessor, 5 hides in Lilford were the property of Thurchil, who held them freely. They had probably been afterwards granted to Waltheof, Earl of Huntingdon, who married Judith, the Conqueror's niece. Judith continued to hold in 1086 (fn. 2) after the execution of her husband in 1075. Their eldest daughter and coheir Maud was given in marriage by William to his Norman follower Simon de St. Lis or Senliz, who was made Earl of Northampton and Huntingdon, and after his death she was married to David, later king of Scotland, who became Earl of Huntingdon. (fn. 3)

The overlordship then followed the descent of the earldom and honour of Huntingdon. The tenants in demesne were the Oliphants (Olifard, Holyfard) who from being holders of land in England under the kings of Scotland transferred their allegiance to Scotland, becoming magnates and peers there. (fn. 4) Three branches of the family apparently held lands within the counties of which the King of Scotland was earl. The earliest member of the family as yet found is Roger Oliphant who witnessed a charter of Simon de St. Liz to St. Andrew's Priory, Northampton, not later than 1108. (fn. 5) In the survey of the reign of Henry I (1100–35) William Oliphant was holder of 5 hides in Lilford of the king of Scotland and was living about 1147. (fn. 6)

He was probably succeeded by David Oliphant godson of King David of Scotland, who assisted at King David's escape after the rout at Winchester in 1141. (fn. 7) It was he probably who was attesting charters to 1167. (fn. 8) His successor was possibly William whose name appears in these counties about this time. (fn. 9) Walter Oliphant was given as a hostage by William of Scotland in 1174 (fn. 10) and a William and his sister Agatha were connected with Northamptonshire in 1201. (fn. 11) It was another Walter, probably, whose land in Lilford was in 1216 committed to Ralf de Trubleville. (fn. 12) This Walter was a man of considerable importance in Scotland, holding the office of justice of Lothian and being constantly in attendance on the king. (fn. 13) He presented to the church of Lilford in 1228 (fn. 14) and he (fn. 15) and William (fn. 16) Oliphant were dealing with lands in Lilford and Wigsthorpe in 1232. In 1242–3 the heir of Walter Oliphant (as though Walter were dead) is said to hold one fee in Lilford of the Earl of Albemarle of the Honour of Huntingdon. (fn. 17)

He was probably succeeded by David Oliphant godson of King David of Scotland, who assisted at King David's escape after the rout at Winchester in 1141. (fn. 7) It was he probably who was attesting charters to 1167. (fn. 8) His successor was possibly William whose name appears in these counties about this time. (fn. 9) Walter Oliphant was given as a hostage by William of Scotland in 1174 (fn. 10) and a William and his sister Agatha were connected with Northamptonshire in 1201. (fn. 11) It was another Walter, probably, whose land in Lilford was in 1216 committed to Ralf de Trubleville. (fn. 12) This Walter was a man of considerable importance in Scotland, holding the office of justice of Lothian and being constantly in attendance on the king. (fn. 13) He presented to the church of Lilford in 1228 (fn. 14) and he (fn. 15) and William (fn. 16) Oliphant were dealing with lands in Lilford and Wigsthorpe in 1232. In 1242–3 the heir of Walter Oliphant (as though Walter were dead) is said to hold one fee in Lilford of the Earl of Albemarle of the Honour of Huntingdon. (fn. 17)

This heir was apparently David Oliphant, one of the magnates of Scotland, who in 1244 was returned as holding one fee in Northamptonshire of William de Forz, Earl of Albemarle, and Christine his wife. (fn. 18) It would seem that this David was dead without issue before 1266 when Walter de Moray (Moravia), apparently one of his heirs, presented to the church of Lilford. (fn. 19) Divorgilla his widow, described as Lady of Lilford, held the manor of Lilford for life by gift of Walter de Moray, who reserved the advowson of the church. (fn. 20) Divorgilla Oliphant gave to Divorgilla daughter of Sir Walter Montfichet (Montefixo) all the lands in Armiston which she held by gift of Roger Wallenger, with remainders to Divorgilla Montfichet's brothers Laurence and John. (fn. 21) In 1287 William Montfichet, Lord of Kirgill (Kirkhill) in Scotland, and heir of the Lady Divorgilla Oliphant, Lady of Lilford, granted the lands he had received from her to Laurence son of Sir Walter de Montfichet, his kinsman, with reversion to John son of the said Laurence. (fn. 22) In 1296 Divorgilla claimed the advowson of the church of Lilford against William son of Walter de Moray, and the King presented because the lands of Scottish magnates had been taken into his hands. (fn. 23)

However, in 1299, the presentation was quashed as having been made in error, the patronage belonging to William de Moray. (fn. 24) In 1300 the manor and advowson of Lilford were conveyed by William de Moray to Anthony Bek, the famous Bishop of Durham, (fn. 25) and he bequeathed them at his death in 1310 to his great nephew Sir Robert de Willoughby, first Lord Willoughby of Eresby, and Margaret his wife, daughter of Edmund Lord Deyncourt, (fn. 26) Sir Robert being son of Alice wife of Sir William de Willoughby and daughter of John Bek of Eresby, brother of the bishop. (fn. 27) Sir Robert de Willoughby obtained confirmation of his title (fn. 28) and in 1316 was returned as holding Lilford and its members. (fn. 29) He died in the same year seised, jointly with his wife Margaret, of the manor and advowson held of John de Britanny as of the Honour of Huntingdon by the service of one knight's fee, his heir being his son John aged 15 years. (fn. 30) John de Willoughby confirmed a grant of the manor for life to William de Willoughby and in 1330 was called upon to justify his claim to soc and sac, tol and theam, infangenthef and outfangenthef, free warren, view of frank-pledge, freedom from pontage, tolls, sheriff's aids, etc., in Lilford. (fn. 31) John de Willoughby was returned as holding half a knight's fee in Lilford in 1346. (fn. 32) He was present at the battle of Crecy in that year and died in 1349. (fn. 33)

He was succeeded by his son Sir John de Willoughby, third Lord Willoughby, who settled the manor of Lilford and its member Hockington in 1361. (fn. 34) He took part in the battle of Poitiers and died in 1372, having settled the manor on his son Robert, fourth Lord Willoughby, and Robert's second wife Margaret, daughter of William Lord Zouche of Haringworth. (fn. 35) He re-settled the manor and advowson in 1376 (fn. 36) and in 1384 he and his wife Margaret granted the advowson to Sir John Holt and others. (fn. 37) He died seised of the manor in 1396 and was succeeded by his son William, fifth Lord Willoughby. (fn. 38) William died in 1409 leaving a son Robert, sixth Lord Willoughby. (fn. 39) The manor of Lilford had, however, been settled for life on Joan widow of William, who after his death married Henry, Lord Scrope of Masham, and later Sir Henry Brounflete. She died in 1434, (fn. 40) when Robert sixth Lord Willoughby succeeded. He was engaged in the wars in France, being present at Agincourt, and died in 1452.

He was succeeded by his son Sir John de Willoughby, third Lord Willoughby, who settled the manor of Lilford and its member Hockington in 1361. (fn. 34) He took part in the battle of Poitiers and died in 1372, having settled the manor on his son Robert, fourth Lord Willoughby, and Robert's second wife Margaret, daughter of William Lord Zouche of Haringworth. (fn. 35) He re-settled the manor and advowson in 1376 (fn. 36) and in 1384 he and his wife Margaret granted the advowson to Sir John Holt and others. (fn. 37) He died seised of the manor in 1396 and was succeeded by his son William, fifth Lord Willoughby. (fn. 38) William died in 1409 leaving a son Robert, sixth Lord Willoughby. (fn. 39) The manor of Lilford had, however, been settled for life on Joan widow of William, who after his death married Henry, Lord Scrope of Masham, and later Sir Henry Brounflete. She died in 1434, (fn. 40) when Robert sixth Lord Willoughby succeeded. He was engaged in the wars in France, being present at Agincourt, and died in 1452.

His heir was his daughter Joan, the wife of Richard de Welles, (fn. 41) seventh Lord Welles, who was summoned to Parliament in her right as Lord Willoughby, retaining this title apparently after her death in 1460. The paternal estates of her husband, forfeited by the attainder of his father Lyon or Leo, Lord Welles, slain at the battle of Towton, where he fought on the Lancastrian side, were restored to him in 1464–5, and in 1468 he obtained full restitution in blood and honours. But in 1469 he, his son-in-law Sir Thomas Dymock, and his son and heir, Sir Robert de Welles, were all beheaded near Stamford, in consequence of the latter's participation in the Lincolnshire rebellion. (fn. 42)

The heir of Sir Robert de Welles (whose execution followed that of his father) was his sister Joan, who, being then the childless widow of Richard Piggott of London, married as her second husband Richard Hastings, brother to William, Lord Hastings, Chamberlain of the Household to Edward IV. (fn. 43) A faithful Yorkist, he obtained a grant in 1470 of the lands his wife would have inherited but for the attainder of her father and brother. Lilford and its member, as conveyed to himself and his wife Joan by grant of Thomas Fitzwilliam, senior, and Thomas Fitzwilliam, junior, (fn. 44) were expressly excepted from the act of attainder and forfeiture against Richard Lord Welles, his son Lord Robert, and his sons-in-law Thomas de la Laund and Sir Thomas Dymock and others, and from the petition for its repeal presented in 1485 (fn. 45) by the heirs of Lord Welles.

In 1473 Lilford was conveyed by Sir Richard Hastings, kt., and Joan his wife, daughter and heir of Sir Richard Welles, kt., sometime Lord de Welles and Willoughby, to William Brown of Stamford, John Brown of Stamford, Sir William Stoke, kt., Thomas Stoke, clerk, John Elmes of Henley-on-Thames, and William Est. (fn. 46) In 1475 an exemplification was obtained at the request of William Brown of Stamford, wool merchant, of the article in the act of attainder exempting Lilford from its operation, as being at the date of the passing of the act in the hands of the Fitzwilliams, by whom it had been conveyed as above to Sir Richard Hastings and his wife, who afterwards sold it to the said William. (fn. 47).

As already stated, this William Brown married Margaret (nee Stock), so that his descendants inherited Papley, Lilford (which he acquired in 1473) and a large estate in Warmington and the surrounding country. He was from Stamford, where he founded an almshouse called the Bedehouse. He died 14 April, 1489, having made a will in which he desired to be buried in Our Lady's chapel in All Hallows', Stamford. Margaret, his widow and executrix, survived but a short time, dying on 28 October, 1489. (fn. 48). The heir was their daughter Elizabeth, wife of John Elmes, aged 48 and more. Margaret's will left many gifts to churches, including a vestment of black velvet for Warmington (cope, chasuble and two tunicles); it mentions John Elmes the elder, my son, and Elizabeth his wife, William, Katherine, John the younger, Joan and Isabel Elmes, Thomas, Margaret and Jane Fazakerley, and the executors were her brother Thomas Stock, clerk, John Elmes and William his son.

John Elmes, son of John Elmes of Henley, died 4 May, 1491, and it appears by the inquisition that he had married Elizabeth by 1457; their son and heir William was 27 years old. Elizabeth and William Elmes obtained the manors of Lilford and Papley and other estates from Brown's trustee in 1495. Thomas Stock died 23 October, 1495, leaving as heirs his sister Isabel Fazakerley and his niece Elizabeth Elmes. Elizabeth survived till 1511, but her son William Elmes, of Stamford and the Inner Temple, died in 1504, having by his will made many charitable gifts, including one to Warmington. The will mentions his mother Elizabeth, his wife Elizabeth and Joan Iwardby her mother, sons John and Thomas, and daughters Elizabeth and Joan. He desired to be buried in the Temple church in London. His wife was one of the three daughters and coheirs of John Iwardby of Great Missenden, Bucks, where she was born 24 August, 1475. She seems to have died in 1526.

The son, described as John Elmes of Lilford, esq., made his will, a very long one, in November, 1540, and it was proved 7 February, 1544–5. By it he left £10 to his 'grandfather' William Brown's almshouses at Stamford and small gifts (including 6s. 8d. to Warmington) to many churches, the gild of our Lady at Oundle, etc. His son Edmond was under 22 years of age, and other children and kinsfolk are mentioned; also lands in Lilford, Papley, Ogerston, Elton, Fotheringhay and Stamford. The executors were desired to make reparation for any wrongdoing by him, and to give knowledge of this 'about Oundle and Stamford, where I shall be most defamed.' His wife, who survived, was Edith, daughter of John, lord Mordaunt of Turvey, Beds. In 1539 charges had been brought against him in the Star Chamber, which may explain the defamation mentioned in his will. The inhabitants of Lilford, Warmington and Barnwell claimed common of pasture in these places, and alleged that Elmes had closed up highways in Papley, etc., converted arable into pasture and impounded their cattle. He was learned in the law and a man of great lands and substance. The witnesses for complainants described Papley as a hamlet in Warmington, and the inhabitants of Warmington had common there till Elmes stopped them. Once there had been twelve ploughs going in the fields of Papley, but now only three. There had been ten houses of husbandmen and four cottages in Papley, but only two houses were now inhabited. Elmes had surcharged the fields with cattle and sheep. He had stopped the highway from Huntingdon to Fotheringhay called Bradgate, and other roads.

The son Edmund succeeded in 1543, and made in 1579 a settlement of his manors of Lilford, Papley and Warmington (this latter being the Stock estate); and he died 12 March, 1601–2, holding these manors of the bishop of Peterborough, having settled them on his second son Thomas. The heir was a son John, then aged 40. No reason is given for thus giving them to a younger son, but his widow Alice (sister of Oliver St. John of Bletsoe) in her own will directed that her late husband's will was to be carried out, and left household stuff at Lilford to John on condition that he did not disturb it; Thomas was to have the household stuff at Papley. Thomas Elmes, who thus succeeded, had already several children—William, John, Edmund, Thomas and Anthony being named.

The son Edmund succeeded in 1543, and made in 1579 a settlement of his manors of Lilford, Papley and Warmington (this latter being the Stock estate); and he died 12 March, 1601–2, holding these manors of the bishop of Peterborough, having settled them on his second son Thomas. The heir was a son John, then aged 40. No reason is given for thus giving them to a younger son, but his widow Alice (sister of Oliver St. John of Bletsoe) in her own will directed that her late husband's will was to be carried out, and left household stuff at Lilford to John on condition that he did not disturb it; Thomas was to have the household stuff at Papley. Thomas Elmes, who thus succeeded, had already several children—William, John, Edmund, Thomas and Anthony being named.

Thomas Elmes made settlements of the manor of Papley in 1615 and 1621; and died at Lilford, 10 July, 1632. As already stated, he had divided his estates, leaving the older manors of Lilford and Papley to his eldest son William, then aged 40 or more, and the newly purchased manor of Warmington to the younger son Thomas. William had in 1614 married Margaret, daughter of Sir Francis Goodwin. The manor of Papley was held of the bishop of Peterborough in socage. The rectory of Warmington descended with it for a time. William Elmes suffered a recovery of his manors of Papley, Lilford and Wigsthorpe watermill, etc., in 1632, and died 17 April, 1641, leaving a son and heir Arthur, aged only ten years.

Arthur Elmes and Jane his wife were in 1663 still in possession of the manors of Lilford, and Papley and the rectory of Warmington. Arthur died in that year without children, and Jane married Sir Francis Compton, the Papley and Wigsthorpe estates being sold in 1668 to Edward (Watson), Lord Rockingham, and the Lilford estate descending separately.

Jane, widow of Arthur Elmes, had a life interest in the manor which she and her husband conveyed to Sir John Langham, kt. and bart. in 1666. (fn. 49) Since Arthur Elmes had died without issue, he was succeeded by his cousin Thomas Elmes, the eldest son of Anthony Elmes of Greens Norton, brother of Thomas Elmes who died in 1632. He was knighted as Thomas Elmes of Lilford in 1688 (fn. 50) and died in 1690. He was succeeded by his brother William Elmes, who made various settlements of the manor of Lilford cum Wigsthorpe and the advowson. (fn. 51) He died in 1699, 'the last male branch of that ancient and honourable family of the Elmes.' (fn. 52)

John Adams and other trustees under the abovementioned settlements conveyed the manors of Lilford and Wigsthorpe, the rectory and advowson, to Sir Thomas Powys in 1711, who took a fine of them in 1713. (fn. 53)

Sir Thomas Powys, the second son of Thomas Powys of Henley (co. Salop) and of Anne daughter of Sir Adam Littleton, was the judge who conducted the trial of the Seven Bishops in 1688. He died in 1719, and was buried at Lilford. (fn. 54) Thomas, his eldest son by his first wife Sarah, daughter of Ambrose Holbech (co. Warwick), who succeeded him, married Catherine, daughter and heir of Thomas Ravenscroft of Broadlane (co. Flint), and died in 1720. His son and heir, also named Thomas, married Henrietta daughter of Thomas Spence, Serjeant of the House of Commons. (fn. 55) He was succeeded by his son Thomas, who was M.P. for the county from 1774–97. A man of great parliamentary talents and distinguished integrity, he was one of the batch of peers created during the ministry of William Pitt in 1797, being created Baron Lilford on 26 October. He married Mary, the daughter of Galfridus Mann, and died in 1800.

Sir Thomas Powys, the second son of Thomas Powys of Henley (co. Salop) and of Anne daughter of Sir Adam Littleton, was the judge who conducted the trial of the Seven Bishops in 1688. He died in 1719, and was buried at Lilford. (fn. 54) Thomas, his eldest son by his first wife Sarah, daughter of Ambrose Holbech (co. Warwick), who succeeded him, married Catherine, daughter and heir of Thomas Ravenscroft of Broadlane (co. Flint), and died in 1720. His son and heir, also named Thomas, married Henrietta daughter of Thomas Spence, Serjeant of the House of Commons. (fn. 55) He was succeeded by his son Thomas, who was M.P. for the county from 1774–97. A man of great parliamentary talents and distinguished integrity, he was one of the batch of peers created during the ministry of William Pitt in 1797, being created Baron Lilford on 26 October. He married Mary, the daughter of Galfridus Mann, and died in 1800.

His son Thomas succeeded him at Lilford, as second baron. Thomas Atherton Powys, third baron, inherited Lilford at his father's death in 1825. (fn. 56) The Lilford estates, increased by a succession of inheritances, to which the eventual inheritance from Sir Littleton Powys, elder brother of its purchaser Sir Thomas, must be added, were, after the death of Thomas Powys, third Baron Lilford, at Lilford Park in 1861, dealt with by the Lilford Estate Act, passed on 29 July 1864, (fn. 57) as the result of a Chancery suit instituted by his son Thomas Littleton Powys, the fourth baron, for the purpose of amending the will of his father, dated 24 February, 1841. From the operation of this Act, Lilford, with its chief messuage, park and pleasure grounds, was expressly excluded. It was as an ornithologist that the fourth baron, one of the founders of the Ornithologists' Union, left his mark on Lilford, (fn. 58) the valuable collections he made being housed there. He travelled much, and wrote on his subject. After being twice married he died in 1896.

He was succeeded by his son John, the fifth baron. After the death of John Powys in 1945, his brother Stephan succeeded as the sixth baron, but died in 1949 without issue thus ending this branch of the Powys family. After 1949, Lilford Hall remained empty for around 50 years.

The Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem near Clerkenwell had a preceptory at Dingley as early as the reign of King Stephen, with lands valued in 1535 at £108 13s. 5½d. (fn. 59) In 1330 the prior of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem claimed view of frankpledge in Glapthorn from his tenants in Fotheringhay, Lilford, etc.; (fn. 60) and on 18 August 1542 a messuage in the tenure of William Whyte of Lilford, which had belonged to the preceptory at Dingley, was granted to Robert Tyrwhitt, the king's serjeant, with meadow lands, rent, etc. (fn. 61)

Lilford Church

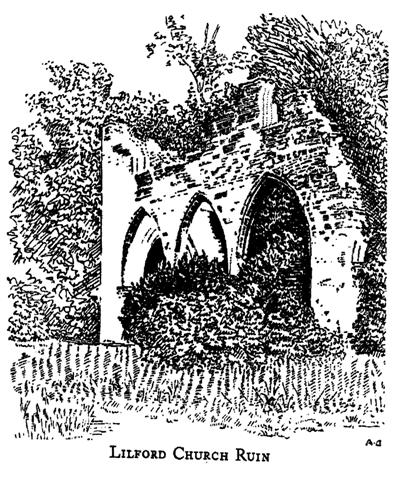

The church of St. Peter was taken down in 1778, and no part of it remains on the site. (fn. 62) Three arches from the nave arcade were, however, set up in The Lynch, below Achurch, close to the river, and the monument to Sir Thomas Powys was removed to Achurch church. According to Bridges, (fn. 63) the church of Lilford consisted of chancel, nave, north and south aisles, and west tower and spire, but part of the south aisle appears to have been taken down before his time. (fn. 64) There were four bells in the tower. The registers began in 1560, the first volume containing all entries to 1778, together with a long list of briefs (1712–54), and accounts of perambulations of the parish in 1718, 1722 and 1726. A vicarage house was built in 1714. The communion plate is now at Achurch.

The church of St. Peter was taken down in 1778, and no part of it remains on the site. (fn. 62) Three arches from the nave arcade were, however, set up in The Lynch, below Achurch, close to the river, and the monument to Sir Thomas Powys was removed to Achurch church. According to Bridges, (fn. 63) the church of Lilford consisted of chancel, nave, north and south aisles, and west tower and spire, but part of the south aisle appears to have been taken down before his time. (fn. 64) There were four bells in the tower. The registers began in 1560, the first volume containing all entries to 1778, together with a long list of briefs (1712–54), and accounts of perambulations of the parish in 1718, 1722 and 1726. A vicarage house was built in 1714. The communion plate is now at Achurch.

Advowson

The presentation to the church was made in 1228 by Walter Oliphant, and the early history of the advowson is to be found with that of the manor (q.v.), with which it was held until, in 1383–4, Robert de Willoughby of Eresby and his wife Margaret made a conveyance of land in Lilford and of the advowson to Sir John Holt, kt., and others, from whom they were acquired in 1387 by John de Buckingham, Bishop of Lincoln. (fn. 65) The bishop bestowed them as 'bought and acquired with the goods bestowed on him by God,' on the dean and chapter of Lincoln, for the endowment of a chantrey called Buckingham's or Burghersh (Burgherwahas) Chantrey in the cathedral, of two chaplains and two clerks, to pray for the good estate of Pope Urban VI, the King (Richard II), Queen, bishop, etc., and the souls of Edward III, Queen Philippa, the bishop's parents, etc. (fn. 66) In 1398 a vicarage was ordained by the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield (fn. 67) and in 1535 Thomas Palfreman was receiving 20d. for the church of Lilford as chantrist of Bishop John Buckingham. (fn. 68) On 26 September 1552, among much monastic property then granted to Thomas Cecill and Philip Bold, the rectory, church, and advowson of the vicarage of Lilford, late belonging to this chantry, were included. (fn. 69) Before 1558 they had been acquired by Edmund Elmes, who was then holding them with the manor (q.v.) with which since then they have again been held.

Lilford was one of the parishes which received an augmentation of its living under the Commonwealth. (fn. 70) About 1755 Thomas Powys, father of the first Lord Lilford (see above), pulled down such of his tenants' houses as were in Lilford, and built others in their place in Wigsthorpe; he then petitioned the Bishop of Peterborough (alleging as his reason that it was now necessary for the vicar to reside at Wigsthorpe in consequence of the removal thither of the inhabitants) for leave to obtain a conveyance to himself of the old vicarage house in Lilford, and to erect instead, before 1 January 1757, a substantial house of stone for a new vicarage upon a certain piece of land in Wigsthorpe. The bishop gave his consent in an instrument dated 27 March 1756, (fn. 71) but when Thomas Powys died on 2 April 1767, the old vicarage house and lands had not been conveyed to him. By indenture of 21 August 1767 the ground on which the old vicarage formerly stood was conveyed by the vicar and churchwardens of Lilford to his son, the fourth Thomas Powys of Lilford. (fn. 72) He completed the work his father had begun, by obtaining in 1778 an Act of Parliament (fn. 73) authorising the consolidation of the rectory of Achurch and vicarage of Lilford (he was lord of both manors and owner of the advowson in each parish), and the removal out of Lilford parish of both church and vicarage into Achurch. Lilford church was to be pulled down and the materials used for the repair of that of Achurch, the vicarage newly erected in Wigsthorpe to be exchanged for a house and 2 acres of land near the rectory lands in Achurch, and an acre added by him for a graveyard there; this was accordingly done. In this Act it was stated that the parish church of Lilford was falling into decay, and would be an expense to repair, (fn. 74) and it was enacted that as much of the building as Thomas Powys might require should be left as a private chapel to his mansion house, in which the rector of Lilford cum Achurch was to perform divine service, and the rest sold or otherwise applied to repairing Achurch church : the inhabitants of Wigsthorpe and Lilford to be in future rated for repairs with those of Achurch.

Lilford was one of the parishes which received an augmentation of its living under the Commonwealth. (fn. 70) About 1755 Thomas Powys, father of the first Lord Lilford (see above), pulled down such of his tenants' houses as were in Lilford, and built others in their place in Wigsthorpe; he then petitioned the Bishop of Peterborough (alleging as his reason that it was now necessary for the vicar to reside at Wigsthorpe in consequence of the removal thither of the inhabitants) for leave to obtain a conveyance to himself of the old vicarage house in Lilford, and to erect instead, before 1 January 1757, a substantial house of stone for a new vicarage upon a certain piece of land in Wigsthorpe. The bishop gave his consent in an instrument dated 27 March 1756, (fn. 71) but when Thomas Powys died on 2 April 1767, the old vicarage house and lands had not been conveyed to him. By indenture of 21 August 1767 the ground on which the old vicarage formerly stood was conveyed by the vicar and churchwardens of Lilford to his son, the fourth Thomas Powys of Lilford. (fn. 72) He completed the work his father had begun, by obtaining in 1778 an Act of Parliament (fn. 73) authorising the consolidation of the rectory of Achurch and vicarage of Lilford (he was lord of both manors and owner of the advowson in each parish), and the removal out of Lilford parish of both church and vicarage into Achurch. Lilford church was to be pulled down and the materials used for the repair of that of Achurch, the vicarage newly erected in Wigsthorpe to be exchanged for a house and 2 acres of land near the rectory lands in Achurch, and an acre added by him for a graveyard there; this was accordingly done. In this Act it was stated that the parish church of Lilford was falling into decay, and would be an expense to repair, (fn. 74) and it was enacted that as much of the building as Thomas Powys might require should be left as a private chapel to his mansion house, in which the rector of Lilford cum Achurch was to perform divine service, and the rest sold or otherwise applied to repairing Achurch church : the inhabitants of Wigsthorpe and Lilford to be in future rated for repairs with those of Achurch.

Before the passing of the Act the profits of the vicarage of Lilford, exclusive of the vicarage house and a small homestead thereto belonging, consisted in some small tithes and a right of common belonging to the vicarage house, for which the lord of the manor paid in 'nature of a composition' £65 yearly. Under the Act of 1778 it was agreed that 65 acres called Wigsthorpe Little Wold, and 46 acres, the east part of a piece of ground called Wigsthorpe Great Wold contiguous, should be vested in the rector of Achurch in lieu of all tithes. An exchange was also effected of the vicarage and land in Wigsthorpe already referred to for a house and lands in Achurch. (fn. 75)

Before the passing of the Act the profits of the vicarage of Lilford, exclusive of the vicarage house and a small homestead thereto belonging, consisted in some small tithes and a right of common belonging to the vicarage house, for which the lord of the manor paid in 'nature of a composition' £65 yearly. Under the Act of 1778 it was agreed that 65 acres called Wigsthorpe Little Wold, and 46 acres, the east part of a piece of ground called Wigsthorpe Great Wold contiguous, should be vested in the rector of Achurch in lieu of all tithes. An exchange was also effected of the vicarage and land in Wigsthorpe already referred to for a house and lands in Achurch. (fn. 75)

A chapel was at one time in existence at Wigsthorpe, the presentation in 1347 being made to 'the church of Lilford with the chapel of Wygesthorp.' In Bridges' time no trace of this chapel remained. (fn. 76)

Charities

Richard Ragsdale by his will dated 30 Jan. 1711 charged his land and hereditaments in Bythorne and Thorpe Achurch with 20s. yearly for the poor of Lilford. 20s. is received yearly in respect of this charge and distributed by the churchwardens to the poor on St. Thomas's Day.

William Lassells by will dated 9 Sept. 1770 gave £100, owing to him on a mortgage of the tolls of the turnpike road between Market Harborough and Brampton to be applied in 'putting apprentice' poor children of Wigsthorpe. The principal sum has increased to £164 9s. 9d.

Footnotes

1 The poll books show there was one freeholder in the parish in 1705, Richard Bailey, and that in 1831 the vicar, the Hon. Fredk. Powys, clerk, the one freeholder, resided at Achurch.

2 V.C.H. Northants. i, 354a.

3 Farrer, Honours and Knights' Fees, ii, 296.

4 V.C.H. Northants. i, 291.

5 Round, Feud. Engl. 223–4.

6 V.C.H. Northants. i, 365b; see also ibid. 291.

7 Farrer, op. cit. 354.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid. 355.

11 Curia Reg. R. ii, 73.

12 Farrer, loc. cit.

13 Bain, Cal. Doc. Scotl. 144, 239.

14 Bridges, Hist. Northants. ii, 242.

15 Feet of F. Northants. case 172, file 25, no. 285.

16 Ibid. no. 284.

17 Bk. of Fees, 938.

18 Farrer, loc. cit.

19 Bridges, loc. cit.

20 Farrer, loc. cit.

21 Buccleuch Deeds, F. 1, 2, 4, 5.

22 Ibid.

23 Bain, Cal. Doc. Scotl. ii, 725; Cal. Pat. 1292–1301, p. 184.

24 Ibid. 444; Bain, op. cit. 1104.

25 Feet of F. Northants. 28 Edw. I, case 175, file 58, no. 386.

26 Cal. Pat. 1307–13, p. 375.

27 G.E.C. Complete Peerage, viii, 141.

28 Chart. R. 4 Edw. II, m. 1, no. 10; Cal. Chart. 1300–26, p. 181; Cal. Pat. 1307–13, p.375; cf. Plac. Abbrev. (Rec. Com.), 311.

29 Feud. Aids, iv, 28.

30 Chan. Inq. p.m. 10 Edw. II, no. 78; Cal. Inq. Ed. II, vi, no. 60.

31 Plac. de Quo Warr. (Rec. Com.), 575–6.

32 Feud. Aids, iv, 449.

33 Bridges, op. cit. ii, 241.

34 Harl. Chart. 58, A. 48.

35 Chan. Inq. p.m. 46 Edw. III (1st nos.), 78.

36 Harl. Chart. 58, B. 9, 20.

37 Feet of F. Northants. 7 Ric. II, case 178, file 87, no. 60.

38 Chan. Inq. p.m. 20 Ric. II, no. 54.

39 Ibid. 11 Hen. IV, no. 29.

40 Ibid. 12 Hen. VI, no. 43.

41 G.E.C. Complete Peerage.

42 Ibid.; Rolls of Parl. vi, 145a, 287a.

43 G.E.C. op. cit. viii, 78.

44 Rolls of Parl. vi, 145a.

45 Ibid. 287a.

46 Feet of F. Div. Cos. Hil. 12 Ed. IV, file 76, no. 90. Wm. Brown had married the daughter and heir of John Stoke of Warmington, by which marriage Warmington became his.

47 Cal. Pat. 1467–77, p. 508. Joan died s.p. 1504–5.

48 Cal. Inq. Hen. VII, i, nos. 476, 478, 525, 533.

49 Feet of F. Northants. Mich. 18 Chas. II; Recov. R. Mich. 18 Chas. II, ro. 29.

50 Bridges, op. cit. ii, 243, cit. M.I.; Harl. MS. 1553, fol. 41; Shaw, Knights of Engl. ii, 264.

51 Recov. R. Mich. 3 Wm. & M. ro. 7, 286; Trin. 5 Wm. & Mary, ro. 7.

52 M.I.

53 Feet of F. Northants. Hil. 11 Anne.

54 Dict. Nat. Biog.

55 G.E.C. Complete Peerage, v, 80.

56 G.E.C. loc. cit.

57 Priv. Stat. 27–8 Vict. c. 10.

58 Lord Lilford, F.Z.S. Memoir by his sister, Mrs. Drewitt.

59 Dugdale, Mon. Angl. vi, 802.

60 Plac. de Quo Warr. (Rec. Com.), 532.

61 Pat. R. 34 Hen. VIII, pt. 6, m. 30; L. and P. Hen. VIII, xvii, g. 714 (15).

62 An engraving of 'Lilford, near Oundle, taken from Ay Church' dated 1757, shows the church standing a short distance to the south-east of Lilford Hall. The tower was of three stages, surmounted by a spire. In 1310 an indulgence was granted to those visiting the altar of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the parish church of Lilford and giving to the fabric of the church or maintenance of the chaplain serving that altar (Linc. Epis. Reg. Memo Dalderby, 161.)

63 Hist. Northants. ii, 242.

64 Among the monuments were a freestone figure of a priest on a tomb in the chancel, a brass tablet—to Arthur Devenshyre (1573) and Oseth his wife (1574)—a stone with a brass inscription torn off, and others to members of the Elmes and Powys families; Bridges, op. cit. 243–35. The dimensions of the building are given as follows: church and chancel 102 ft. 2 in. long, body and aisles 48 ft. broad, tower 12 ft. by 9 ft. 10 in.

65 Chan. Inq. p.m. 8 Ric. II, no. 42.

66 Cal. Pat. 1385–9, pp. 312, 375.

67 Linc. Epis. Reg. Memo. Buckingham, iii, 482.

68 Valor Eccl. (Rec. Com.), iv, 9.

69 Pat. R. 6 Ed. VI, pt. 9.

70 Cal. S.P. Dom. 1658–59, p. 274.

71 Close R. 7 Geo. III, pt. 23, no. 17.

72 Ibid.

73 Publ. Stat. 18 Geo. III, c. 9.

74 Before the increase of their estates recorded in the history of the manor, the Powys lords of Lilford had not only felt equal to meeting this expense but had in the case of 'Mr. Powys' (by his executors) paved the chancel with Ketton square stones, cornered with black marble; and Sir Thomas Powys, kt., before his death in 1719, had in 1714 with his Lady Elizabeth bestowed on it 'a new altar piece, written and painted by Mrs. Creed, daughter of Sir Gilbert Pickering, in the seventieth year of her age, with the communion table, railing, a piece of plate, a pulpit cloth and table cloth of green tabby': Bridges, Hist. Northants. ii, 246.

75 Then in the occupation of Joseph Weed.

76 Bridges, Hist. Nortbants. ii, 241. Source: 'Parishes: Lilford-with-Wigsthorpe', A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 3 (1930), pp. 227-231.