Full Architectural History of Lilford Hall

Introduction

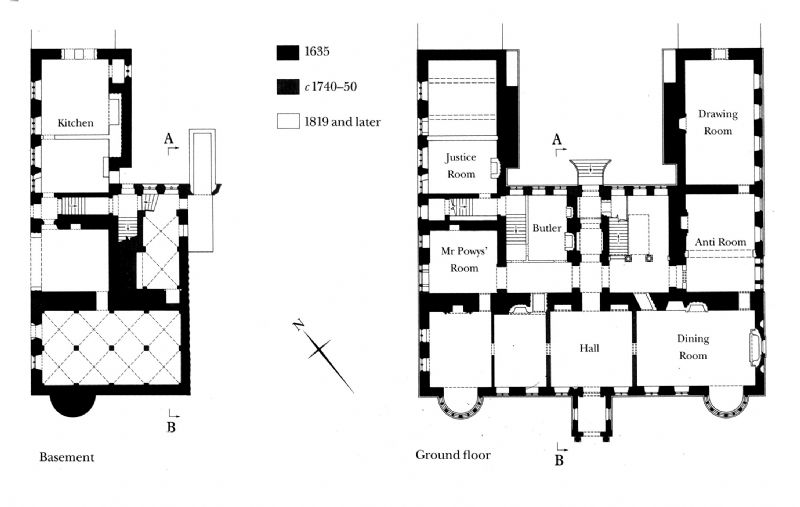

The present house at Lilford was started as a Tudor mansion in 1495, and presently forms the north part of the Front Wing. The south part of the Front Wing as well as both the South Wing and North Wing were built in one campaign and is dated 1635. In plan and elevation it marks a significant phase in the development of the country house between the relatively sprawling H or half-H plan still popular in the early 17th century and the compact rectangular block typical of the mid century, exemplified by Thorpe Hall near Peterborough. Lilford’s single show-front with low wings at the back for service and minor apartments, formed a U-shaped plan. The house is large, outdoing nearby Kirby Hall in the height and floor area of the principal apartments (fn 1).

Lilford retained the traditional accommodation of a hall entered through a screens passage, a great chamber, here placed over the hall, and a long gallery (fn 2). The restrained but finely executed style of the elevations resembles contemporary work at nearby houses such as Apethorpe, Lyveden and Rushton, especially in such features as the shaped gables, though the tall windows with double transoms look back to such work of the 1580s as Bughley House, Stamford.

Lilford retained the traditional accommodation of a hall entered through a screens passage, a great chamber, here placed over the hall, and a long gallery (fn 2). The restrained but finely executed style of the elevations resembles contemporary work at nearby houses such as Apethorpe, Lyveden and Rushton, especially in such features as the shaped gables, though the tall windows with double transoms look back to such work of the 1580s as Bughley House, Stamford.

In the 18th century matching service and stable pavilions were added to the north of the house and the north front given more emphasis as an entrance. The interior was rearranged and extensively remodelled by Henry Flitcroft in the 1740’s. Few 17th-century fittings survived this and the subsequent redecoration and enlargement of the house which took place in the 1840s and again c1909.

Ownership

The Manor of Lilford was bought in 1473 by William Browne, a wealthy Stamford merchant, whose fortune and property outside Stamford were inherited in 1489 by his grandson William Elmes (the elder). William Elmes (the elder) began building the present house in 1495 soon after inheriting the estate, and William Elmes (the younger) greatly extended such in 1632. Another William Elmes died in 1699 the last of the senior branch of the Elmes family.

In 1711 the house was bought by Sir Thomas Powys (1649-1719), former Solicitor-General and younger son of a Shropshire landowner. Bridges, writing shortly after the death of Sir Thomas, indicated that he was responsible for extensive improvements to the house (fn 3). His grandson Thomas (1719-67) inherited Lilford in 1720 and a Shropshire estate in 1731. On coming of age he employed Henry Flitcroft to modernise Lilford. His son Thomas (1743-1800) was created Baron Lilford in 1797.

The house remained with the family until 1990 with the 7th Lord Lilford. Lilford Hall has remained empty for 50 years.

Architectural development

The apparent clarity of the principal elevations of the house conceal a complicated plan on several levels. The main south front (Fig 1) has two equal storeys with gabled attics, rising higher than the side wings to the north although that to the north-west contains a basement and mezzanines. The masonry is dressed rubble with stone-slated roofs. The fenestration is of a consistent design, mostly of two lights with ovolo-moulded mullions and transoms, though of three lights on the west. Some windows on the south front and in the west range have old-fashioned cavetto mouldings with a roll towards the room. This is not necessarily reused or earlier fabric (fn 4).

.jpg) The entrance front is given emphasis by three elaborate shaped gables, linked by balustrades, windows with double transoms on both floors, tall circular bay windows at each end and a central porch with a round-headed arch flanked by Doric columns. The front is crowned by a row of 13 chimney-stacks, an original feature although the stacks themselves have been rebuilt. The side elevations are asymmetrical, with a shaped gable at the south end and, on the west, three further plain gables and on the east two. The former north gables of both wings were also plain. They were replaced when the wings were extended in 1909. The courtyard they enclose, though open on the north side, is relatively constricted, being dominated by large stacks on the courtyard side of each wing.

The entrance front is given emphasis by three elaborate shaped gables, linked by balustrades, windows with double transoms on both floors, tall circular bay windows at each end and a central porch with a round-headed arch flanked by Doric columns. The front is crowned by a row of 13 chimney-stacks, an original feature although the stacks themselves have been rebuilt. The side elevations are asymmetrical, with a shaped gable at the south end and, on the west, three further plain gables and on the east two. The former north gables of both wings were also plain. They were replaced when the wings were extended in 1909. The courtyard they enclose, though open on the north side, is relatively constricted, being dominated by large stacks on the courtyard side of each wing.

The original plan, despite much alteration, can be reconstructed (Fig 2). The single-storey hall appears to have occupied the entire east half of the south front and to have been entered by a screens passage opening from the porch. The present step up into the bow at the east end indicates that there was a dais, an unusual feature at so late a date. There are two rooms to the west of the screen that immediately west of the entrance was, by the mid 18th century, the Dining Room and the next room, lit by the bow, was a small parlour or with-drawing room. This shows that it was no longer considered necessary to place the buttery and pantry immediately next to the hall. These rooms were altered in size and shaped when the later square entrance hall was created.

The line of the original screens passage, subsequently altered to form part of the entrance hall, is prolonged to form a corridor leading to the centre doorway of the north front, with a mezzanine above reached from a secondary staircase. Across the centre of the house runs an axial corridor, to the south of which is a massive spine wall containing the principal flues and stacks. In the east wing on the ground floor there was a small compartment immediately north of the hall, possibly a vestibule to the garden; beyond, were two rooms, possibly parlours or a large apartment.

The line of the original screens passage, subsequently altered to form part of the entrance hall, is prolonged to form a corridor leading to the centre doorway of the north front, with a mezzanine above reached from a secondary staircase. Across the centre of the house runs an axial corridor, to the south of which is a massive spine wall containing the principal flues and stacks. In the east wing on the ground floor there was a small compartment immediately north of the hall, possibly a vestibule to the garden; beyond, were two rooms, possibly parlours or a large apartment.

The main stair is in its original position, though no longer rising, as it did in the 17th century, to the attic. To its west rose a secondary stair, replaced by one of different form in the 19th century, which served the upper floors of the west wing. It could also be reached from the service rooms and by a separate west entrance to the house at basement level from which a flight of stone steps leads up through a round-headed doorway with jewelled keystone. To the north of the landing, in front of the doorway, was a mezzanine room described as an Evidence Room which, presumably, was used for estate business and could be reached by visitors entering from the west side of the house rather by the principal entrance on the south front. The amount of space given to services in the original plan was surprisingly small. Perhaps rooms such as the laundry and the brewhouse were in outbuildings to the west or north which have been removed (fn 5). The kitchen is in the west wing at basement level, rising through one and a half storeys, with a mezzanine above reached from the secondary staircase. The room south of the west entrance has a substantial 17th century stone fireplace and may have served as a steward’s room or servant’s hall. There are cellars under the south-west section of the house but brick vaults inserted in the 18th century destroyed any evidence of the 17th century use.

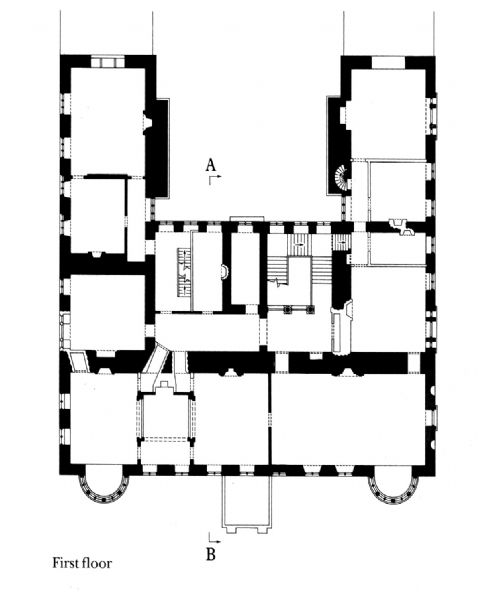

.jpg) The first-floor plan in 1635 was similar to that of the ground floor, with an axial corridor in the main range and the great chamber occupying the area above the hall, though it did not extend to the west above the screens passage. The organisation of the other rooms on the first floor is now uncertain because of later alterations, but in the 1630s it is likely that there was a withdrawing room adjacent to the Great Chamber and possibly three major apartments, at the west end of the south front and in the east and west wings.

The first-floor plan in 1635 was similar to that of the ground floor, with an axial corridor in the main range and the great chamber occupying the area above the hall, though it did not extend to the west above the screens passage. The organisation of the other rooms on the first floor is now uncertain because of later alterations, but in the 1630s it is likely that there was a withdrawing room adjacent to the Great Chamber and possibly three major apartments, at the west end of the south front and in the east and west wings.

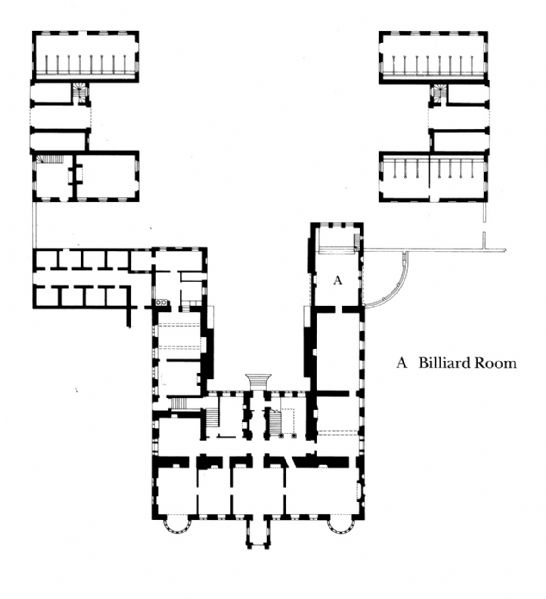

The attics in the side wings contained lodgings of some quality, but the principal room at this level was a long gallery with a plaster barrel vault within the roof of the south range. This could be reached from both stair-cases by two four-centred stone doorways in the spine wall. The gallery was heated by two fireplaces with stone surrounds and was well lit by three large dormers on the south side and a three-light window in each end gable. From the gallery a central doorway on the north side, now blocked, led to a straight flight of steps up through the central stack (the centre flue of the 13 being false) to a flat roof. The decoration of blind shields on the north side of the base of the stack, visible only at this level, indicates the importance of this roof walk (fn 6).

Few fittings of the 1630s have survived the later alterations. Probably the internal doorcases (see Fig 4) and the fireplaces, in plain but well-cut limestone with four-centred heads and stopped mouldings, were the principal features, as in the contemporary houses at Kirby Hall, Lyveden and Apethorpe. One large fireplace in the east wing now has a stone coat of arms of Elmes reset above it in 1909 (fn 7). In the south-west room on the ground floor there is 17th century panelling and a carved wooded surround and over-mantel to the fireplace, altered but possibly always in the house as they fit the height of the room. There was probably never a frieze or cornice even in the principal rooms since the top moulding of the windows was at ceiling level, again as at Kirby.

Few fittings of the 1630s have survived the later alterations. Probably the internal doorcases (see Fig 4) and the fireplaces, in plain but well-cut limestone with four-centred heads and stopped mouldings, were the principal features, as in the contemporary houses at Kirby Hall, Lyveden and Apethorpe. One large fireplace in the east wing now has a stone coat of arms of Elmes reset above it in 1909 (fn 7). In the south-west room on the ground floor there is 17th century panelling and a carved wooded surround and over-mantel to the fireplace, altered but possibly always in the house as they fit the height of the room. There was probably never a frieze or cornice even in the principal rooms since the top moulding of the windows was at ceiling level, again as at Kirby.

Few alterations were made in the late 17th century except for some windows, at both ground and first-floor level on the west front (Fig 5), which were changed from two windows of three lights each to one of two lights and another of four. The latter was of distinctive design with two centre lights below the transom combined into a single light under a semicircular head. This presumably dates to c1660. The ground-floor window was altered again to a more conventional Venetian window in the 18th century. The stone fireplace in the first-floor room may also be of the late 17th century. Its cyma moulding, unlike those of c1635, is unstopped, running down to the floor.

Considerable work was undertaken in the 18th century, first in the eight years of Sir Thomas Powys’ ownership between 1711 and 1719 and then in the 1740s once his grandson had come of age. It is now difficult to distinguish the earlier work from the later. It was perhaps Sir Thomas who was responsible for remodelling the north front to make it a more impressive entrance façade (Figs 6 and 7). However, the doorcase and the small pediment on the upper platband, carried on flat corbels or tabs, seem to crude to belong to the mid 18th century and may be earlier or merely reflect earlier features on the front. A full third storey and flat roof were added. The stable and service pavilions which flank the north front were in existence before 1744 (Fig 8; see Fig 3) but the window details were perhaps changed in the middle of the century. William Freeman, in a diary of 1749, attibutes the work to Flitcroft (fn 8).

.jpg) Henry Flitcroft (1697-1769) is first documented as working at the house in 1744 when he provided designs for an ironwork fence and gateway which were built between the pavilions to close the courtyard on the north side. He altered the house itself between about 1742 and 1750. It was first planned to insert a new screen of three arches in the hall, but this was abandoned in favour of the present arrangement whereby a square entrance hall was created out of the west bay of the hall, the screens passage and the east bay of the former dining room to the west. The new room has a triple arcade on the north and an enriched plaster ceiling. Flitcroft also reconstructed the main stairhall, creating an Ionic colonnade on the south side on both floors, adding plaster enrichments on the walls, and inserting a new staircase with turned balusters.

Henry Flitcroft (1697-1769) is first documented as working at the house in 1744 when he provided designs for an ironwork fence and gateway which were built between the pavilions to close the courtyard on the north side. He altered the house itself between about 1742 and 1750. It was first planned to insert a new screen of three arches in the hall, but this was abandoned in favour of the present arrangement whereby a square entrance hall was created out of the west bay of the hall, the screens passage and the east bay of the former dining room to the west. The new room has a triple arcade on the north and an enriched plaster ceiling. Flitcroft also reconstructed the main stairhall, creating an Ionic colonnade on the south side on both floors, adding plaster enrichments on the walls, and inserting a new staircase with turned balusters.

W G Habershon apparently reworked much of this in 1847 (fn 9). Probably at the same time a winding staircase up to the attic was inserted next to the stack in the east wing because the main stair as rebuilt by Flitcroft rises only to the first floor. He remodelled the attic windows above the bays on the south front by giving the taller centre light a round head to appear as a Venetian window. He designed a shallow stone arch to be added above the bays and below the windows to replace old rotten lintels and to support the weight of the gable above. Inside the gallery he added a round-headed panel to the centre and gable windows to create the effect of Venetian windows but without rebuilding the external face of the masonry (fn 10).

In the east range, the ground-floor windows were reduced in height, sashes inserted and the rooms redecorated with new cornices and fireplaces, several of which survive. The largest room on the east front is carved with swags of leaves and bunches of grapes which implies that it belongs to a dining room. Possibly the rooms were remodelled because the principal rooms of entertainment were moved down from the first floor but, on the first floor, the Great Chamber was given an enriched plaster ceiling though Flitcroft’s decorative scheme is obscured by the elaborate ornament added in the late 19th century or in 1909, when the room was changed from a library to a ballroom.

In the east range, the ground-floor windows were reduced in height, sashes inserted and the rooms redecorated with new cornices and fireplaces, several of which survive. The largest room on the east front is carved with swags of leaves and bunches of grapes which implies that it belongs to a dining room. Possibly the rooms were remodelled because the principal rooms of entertainment were moved down from the first floor but, on the first floor, the Great Chamber was given an enriched plaster ceiling though Flitcroft’s decorative scheme is obscured by the elaborate ornament added in the late 19th century or in 1909, when the room was changed from a library to a ballroom.

To the west two bedrooms were formed with bed recesses back to back. The arches of the recesses survive but the spaces for the beds have been put together to form a dressing room. Again the modillion cornices and other decoration were augmented in the 19th century but the scroll brackets and lion heads on the pilasters flanking the bow in the south-west bedroom appear to be Flitcroft. A triple window, now blocked, in the north wall on the first floor of the west range must also date from this time. The quality of the plaster cornice indicates that this was one of the better suites at this period. On both main floors the axial corridors were rearranged and semicircular arches inserted.

After the work on the house was completed attention turned to the gardens. In 1755 the village, close to the house on the south-west side, was removed and the parish church was demolished in 1788.

.jpg) In 1819 the north room in the east wing was extended by one bay to form a Music Room with a quadrant-shaped conservatory and aviary on the east side. Plans for this work survive but the architect has not been identified. The drawings show that it was only at this stage that the fireplaces in the ground-floor rooms on the south front were moved to the centre of the rooms created by Flitcroft. Shortly afterwards the two-storey extension to the west wing containing service rooms was heightened by a storey and a new roof built balancing the east wing.

In 1819 the north room in the east wing was extended by one bay to form a Music Room with a quadrant-shaped conservatory and aviary on the east side. Plans for this work survive but the architect has not been identified. The drawings show that it was only at this stage that the fireplaces in the ground-floor rooms on the south front were moved to the centre of the rooms created by Flitcroft. Shortly afterwards the two-storey extension to the west wing containing service rooms was heightened by a storey and a new roof built balancing the east wing.

Remodelling by Habershon in 1847 (fn 11) included elaborate gardens walls and gateways around the house. He proposed rebuilding the Music Room and raising the end of the wing to the height of the rest. A shaped gable on the east front was to balance that at the south end. The scheme was not implemented until 1909 when the Music Room was remodelled as a Billiard Room. This has Jacobean-style panelling, an ornate ceiling, a platform at the north end for watching the game and a disguised door in the panelling with a narrow staircase down to the gentlemen’s cloakroom below. The west range was raised to the same height by the addition of a third storey and an attic. Further work at this time presumably included the panelling in the former hall, then used as a dining room, the redecoration of the first-floor bedrooms and the insertion of other elaborate plaster ceilings in a 17th century style.

.jpg)

Primary sources

Plans and drawing relating to 18th and 19th century alterations are in the Northamptonshire Record Office, catalogued 3802-9 (Flitcroft); 3821-3824 (of 1819) and 3837-3838 (Habershon).

Principal published sources

Bridges 1791, The History and Antiquities of Northamptonshire, Volume II, P.241-6 bis

Gotch 1936, The Old Halls and Manor Houses of Northamptonshire P.36-7

Markham, Ca 1909-10. ‘The Elmes family of Lilford’, Northamptonshire Notes and Queries new ser 3, 167-9, 247-9

Victoria County History Northants III, 227

Footnotes

1. The area of the hall (108 sq m) is comparable with other Northamptonshire houses, for example to the hall of Kirby (105 sq m) and Boughton (115 sq m). The Great Chamber (90 sq m) is not so much smaller than that at Castle Ashby (112 sq m).

2. The gallery is an indicatioin of the status of the house though it is old-fashioned in being at attic level, as at Rushton in 1595, rather than on the first floor as at Kirby or Castle Ashby.

3. Bridges 1791, The History and Antiquities of Northamptonshire, Volume II, P.241.

4. For a similar mix of mouldings see the contemporary work at Lyveden New Build.

5. The service court, with brewhouse and stable, is to one side at Castle Ashby, near the kitchen, though it is more common for stable and service blocks to flank the entrance as at Rushton or Easton Neston.

6. It is difficult to reconstruct the form of this roof-walk because of the alterations made on the north front. The flat was on the north side of the stacks and the view would have been to the north towards Oundle.

7. Markham 1909-10, ‘The Elmes family of Lilford’, Northamptonshire Notes and Queries new ser 3, 167.

8. Colvin 1978, A Biographical Dictonary of British Architects 1600-1840 P.312.

9. The staircase was built to Flitcroft’s design for it is shown in its present form on the plans of 1819. It is not clear why the staircase and much of the decoration had to be replaced. (For Habershon, see note 11.)

10. The long gallery was therefore not only retained but remodelled in the mid 18th century.

11. William Gilbee Habershon (1818-91) was employed by Lord Lilford at Bewley Hall, Warrington, Cheshire, and Castle Irwell, Lancashire.